Develop Your Passion

Passions are not gifts assigned to us at at conception or birth or adulthood or any other significant moment in human development. They are developed.

When I was graduating high school, if you had told me that I would have a passion for writing, artful living, and teaching, I would have laughed at you. At that age, I didn’t really want to do any of those things. I had a passion for filmmaking. But I lasted exactly one semester in my university’s film program. That experience taught me that I liked the idea of making movies much more than I actually liked movies. In fact, I struggle with movies nowadays. Unless I’m really into it, I rarely make it to the end of a two-hour film; I tend to fall asleep watching anything that’s longer than a 45-minute television episode.

What happened? How did I lose this passion?

As we grow up, we are often told to "do what we love" and to "find our passion." This is not bad advice, but it very easily sours. When we take this advice to heart, we often begin to believe that there is a single thing out there that we are meant to do, a passion that we are meant to have. In this worldview, passions are like gifts that have been assigned to each of us at birth and our purpose in life is to find that passion and align ourselves with it. We spend years searching for it. Along the way, life happens, we get sidetracked by mortgages and kids and careerism, and before we know it, we’re in our forties and experiencing a full-blown midlife event because we realize that we never discovered our passion!

I should’ve followed my heart!

I should’ve found my passion!

I’ve wasted all these years!

As with most things, whether or not you wasted those years is a matter of perception. If you believe they were a waste, that you got nothing out of them, then that will be true. But if you believe that they were necessary events along the path that has led you to this moment, then they aren’t a waste: they’re necessary!

The core problem with this passion-as-gift philosophy is that it doesn’t take into account the way that humans really work. Human beings become passionate about all sorts of things because that’s how we are wired. We are learning machines who fixate on our environments. This learning ability is the evolutionary advantage that allowed upright, hairless apes to become the world’s most invasive species. But it’s also this learning ability that has allowed human beings to become the universe observing itself.

You are wired to get passionate.

You are wired to take an interest.

Many years ago, I had an opportunity to travel to the Aegean with a group of Harvard Divinity School students. One of the students, during the course of his research, had developed an interest in ancient plumbing. Specifically, he was fascinated by the way that ancient city architects used terra cotta piping to move rain water away from city centers and into cisterns or ditches or rivers.

This guy was fascinated by drainage.

As we traveled around, walking in the footsteps of the ancients, he would, without fail, point at some four-inch, u-shaped indentation in the ground, perhaps with a trace of pottery still there, and exclaim: “Drainage!” Many evenings, we’d sit around the table, sipping ouzo or raki, listening to him talk about the wonders of ancient drainage systems. I even recall attending a birthday party, weeks after the trip, and getting into a conversation with this guy—as he excitedly prepared Turkish coffee for anyone interested—about how he had taken his interest in ancient drainage to the streets of Cambridge. Everywhere he looked, he saw the marvels of drainage systems! Their necessity! Their wonder! Even their beauty…

I can assure you, this grad student was not born with a passion for drainage systems in the ancient Aegean. He did not pop out the womb with some sort of predetermined propensity for plumbing.

Passions don’t work like that. They are not gifts assigned to each of us. They are not these singular life purposes that are handed out at conception or birth or adulthood or any other significant moment in human development.

Passions are developed.

The Latin root of the word passion is the stem pati- which means "to suffer, endure, undergo, or experience." In order to develop your passion, you have to decide what you’re willing to suffer for? What are you going to endure? What will you undergo in order to gain this experience and expertise?

This may, of course, seem at odds with a blog in which I encourage you to be an unruly buddha, but I want to assure you that when I use the word “suffering” here, I’m not talking about suffering in the ordinary, attached, dukkha sense. Instead, I’m talking about effort.

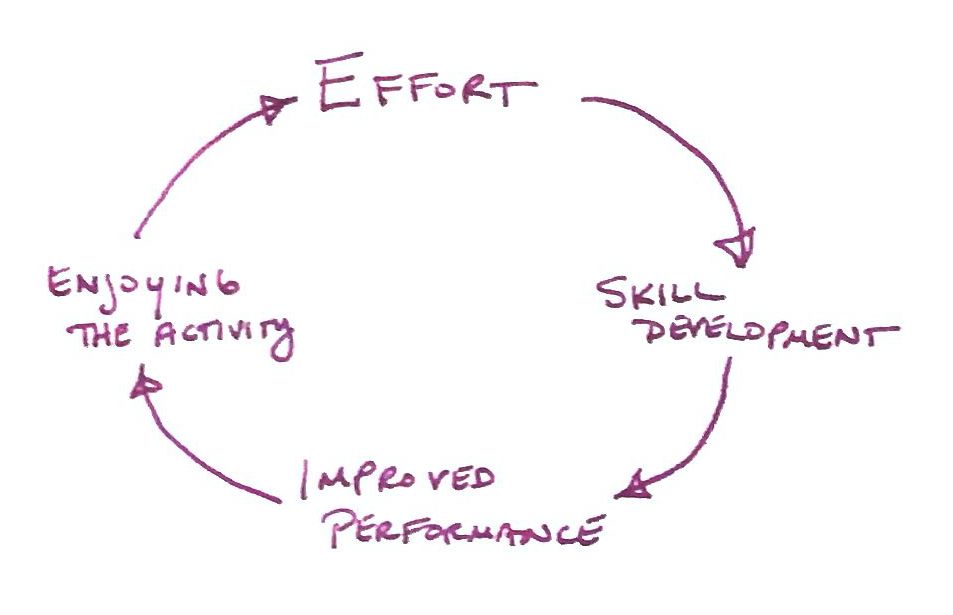

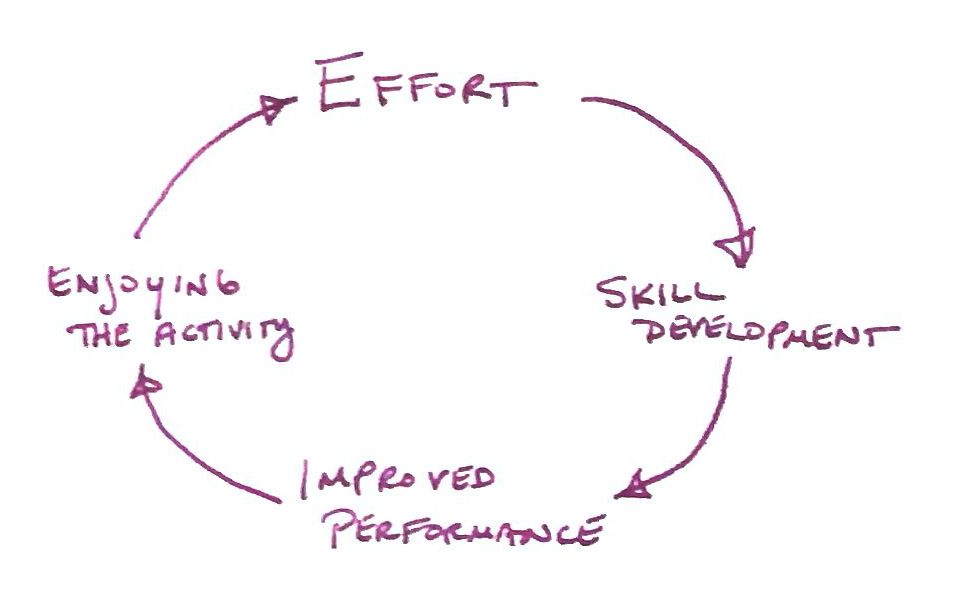

Developing a passion is a cycle.

When we put effort into something, we typically get better at it. Skill development comes from deliberate practice over time. Psychological studies have proven that. As we develop our skills, we get better at things. As we get better at things, we tend to like them more. Why? Well, because I’m really good at this. I like it!

Before we know it, we’ve got a passion on our hands.

That passion may be horseback riding or cooking or ancient Aegean city planning with a special emphasis on drainage systems! But I can guarantee you that anyone who really has a passion for something has worked for that passion.

Practice

Let's spend a few moments taking stock of this passion situation. Grab your journal or a piece of paper or open up your notes app on your fancy device, and do the following:

- Create a list of things in your world—your professional life, your life at home, etc.—that you’ve really had to work for.

- Create a list of things that you’re really good at.

- Spend some time writing out what, if anything, on those lists you’d be willing to put a great deal of effort into for a long period of time.

If you’re able to answer #3, then you’ve already found your passion. Now, you just have to develop it. Years of deliberate practice and effort focused on that one thing, whatever it may be.

Go!